Phil,

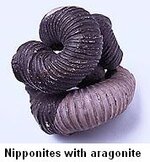

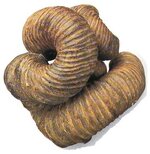

Thanks for the heads-up on this thread. Nipponites is certainly one of the oddest looking heteromorph ammonites, but if you look at in in the context of the family of heteromorphs it belongs to (the Nostoceratidae) it becomes a bit less bizarre. It also helps to know something of the origins of the group.

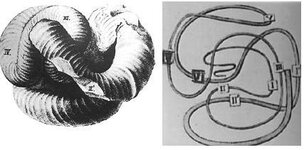

The Nostoceratidae are an offshoot of the Turrilitidae, which come from the Hamitidae. Now, the Hamitidae as adults were flat, either open spiral or paper-clip shaped beasts. But soon after hatching, many of them became helically coiled. The helix went on for two or three complete whorls, then straightened out.

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/hamites.html

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/hamites_attenuatus.html

You also see the same basic shape appearing among another family, the Anisoceratidae, apparently independently.

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/heteroclinus.html

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/anisoceras.html

My guess is the helix was a pre-requisite to the paper-clip shape, allowing the two or three straight shafts to be tucked neatly under the helix. If the helix wasn't there, the shell would bump into itself as the ascending arm of the "u bend" came back to where the spiral was. As luck would have it, the spiral also served the juveniles well during the early drifting stage of their life. It held the animal head downwards, and ambient water currents would cause the shell to rotate, allowing a much more efficient sweeping of the water for food.

Anyway, as time wore on, some ammonites 'concentrated' on this helical phase of life, becoming neotenic, that is, the adult morphology became increasingly similar to the juvenile one. The earlier members of this line (like Hamitella) of evolution had extended helical phases followed by a much shorter final hook than their ancestors. One lineage led to species that lost virtually all traces of the final hook, the only evidence of adulthood being maybe a loosening of the helix and the presence of apertural modifications such as constrictions and thickened ribs. The helix also became increasingly close and pointed.

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/hamitella.html

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/ammonites/turrilitoides.html

This lineage eventually gave rise to the Turrilitidae including things like Turrilites and Mariella. In parallel, the Anisoceratidae produced their own fully-helical forms (the genus Pseudhelicoceras) but apparently that didn't lead to anything and died out at the end of the Albian. See Text Figure 6 in my paper on Albian heteromorph radiations for a summary of this. It's interesting that both groups did this helical coiling thing at the same time, the middle part of the Albian.

http://homepage.mac.com/nmonks/Resources/cladistics_albian_heteros.pdf

The Turrilitidae, with their simple helical shells, do seem to have had functioning siphons for jet propulsion (their shells had "spouts" coming from the aperture like truncated versions of the siphons seen on gastropod shells).

The Nostoceratidae are a specialised offshoot of the Turrilitidae that appeared somewhere close to the Cenomanian - Turonian boundary and survive right to the end of the Cretaceous. They are generally helical initially but then have a hook-shaped living chamber. Unlike the hooks of the Hamitidae, which are in the same plane as the helical coiling, the hooks of the Nostoceratidae are perpendicular to the helix and sort of hang underneath the spiral like a gondola. There are all sorts of variations, but what does appear to be happening is the animals have become completely specialised for a planktonic lifestyle with little if any swimming ability. They do not have the "spouts" seen in the Turrilitidae and in many the final aperture is recurved into the main whorl of the shell.

While the shell coiling was weird, in other regards these are conventional ammonites. The shell is solid, not flexible, and the chambers have the same complex quadrilobate sutures as the other heteromorphs. This is good evidence that they retained the same buoyancy function as other ammonites (so they weren't benthic crawlers at least).

Nipponites is a lot _less_ weird when you see it in context of the entire family it belongs to, the Nostoceratidae. There are clear 'experiments' in finding the right balance between shell shape and orientation, and presumably defence and cost of construction as well. Most the Nostoceratidae (and indeed many other heteromorphs) have shells that can be considered as "stable" -- that is, like a balloon, they are self righting, so that if a water current pushed the aperture upwards, gravity would bring it back down again. Why stability was such a big deal is unclear.

Many also coil in such a way that the initial spirals are hidden inside the later ones, so perhaps defence was an issue. Maybe the thinner, early shell was more vulnerable than the later, thicker shell, and so Nipponites kept the early whorls tucked away inside. Often overlooked is the effect of size on predation: a small but globose shell is less easily attacked than a big, flat one. Midwater predators need to take the thing into their mouths whole, so if something was ball shaped (like Nipponites) it would be difficult to bit compared to something that was flat (like Hamites) that could be bitten much more easily. Among gastropods, this does seem to be the reason for spines rather than spikiness _per se_.

Anyway, the bottom line does seem to be that Nipponites is a genuine species (not a freak) and simply a more extreme example of a family that was doing all kinds of odd things. While they look strange, the fact that the Nostoceratidae were doing so well in the latest Cretaceous does seem to indicate that they were adapting to a changing world that the other ammonites, which were doing badly, were unable to do.

Cheers,

Neale

bizarre!

bizarre!